Heroes, Villains, and History's Gray Areas

A Letter From a Polish Professor That Made Me Think Twice

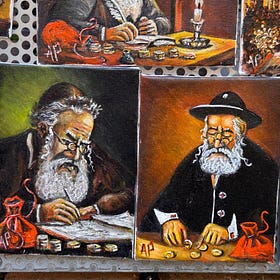

A few months ago, I wrote about my complicated feelings visiting Poland, the homeland of my beloved uncle Shlomo, a Holocaust survivor. The piece explored my discomfort—how I found myself wrestling with a country that was both victim and, in some cases, victimizer during World War II. I felt the weight of history in Krakow's Jewish restaurants, in the paintings of stereotypical Jews clutching coins, in the once thriving Jewish communities where Jews no longer live. My feelings, I learned, aren't unique; many Jews I have spoken with after my essay came out harbour similar feelings about Poland, struggling to separate past from present in a land that was once The Paradise of the Jews.

Wrestling with Poland

Every Mother’s Day, I send out two cards: one to my mother in Montreal and one to my second mother in New York City.

Yet even as I wrote about these feelings, I wondered if I was being fair, if our collective Jewish perspective was too clouded to see the full picture. After all, both Jews and Poles share a history of being caught between empires, of having our sovereignty denied, our culture suppressed. We might have more…