What About Whataboutism?

Last month, I watched the documentary No Other Land about the occupied West Bank. The film follows Palestinian activist Basel Adra as he documents the systematic demolition of the villages of Masafer Yatta in the South Hebron Hills.

I was heartbroken watching families forced from their homes, their water cisterns destroyed, their sons shot. Around me, people sighed audibly watching yet another home or school being bulldozed. It’s worth watching, no matter where you stand on the current conflict.

Yes, like all advocacy, the film presents a particular perspective. But even recognizing its selective lens, the human suffering I witnessed was raw and real. The images of families watching their homes and lives being bulldozed affected me deeply.

And yet, like a moral monster, some tribal part of me immediately sought ways to rationalize it all away.

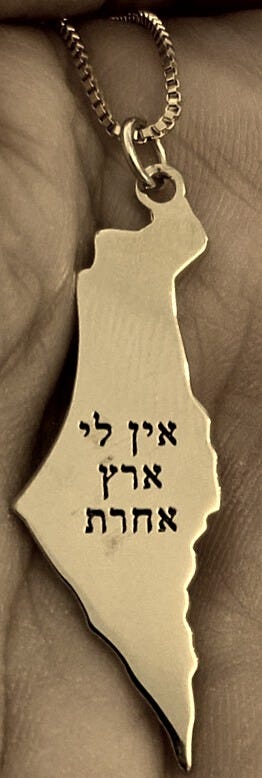

Despite being gutted by these scenes, I found myself scrambling for counterarguments and comparative suffering elsewhere to soothe my unease. First, I thought about the Jewish exodus from Arab lands, in which nearly one million Jews, including my Yemeni grandparents, were expelled or fled from countries their families had lived in for centuries or longer. I found myself comparing the silence around that ethnic cleansing to the global outrage over Israel.

Then I thought of Ehud Barak’s offer of a Palestinian state in 2000 and 2001—rejected by Yasser Arafat. If only he had accepted, these Palestinians wouldn't be facing displacement today.

“What about all that?” a voice in my head asked.

And there it was: whataboutism in action.

Empathy pulled me in one direction, tribal instinct the other. This tension is what got me thinking: when is whataboutism a lazy dodge and when does it serve the truth?

While whataboutism is often rightfully dismissed as a deflection tactic, I've come to believe that the distinction between harmful deflection and legitimate context lies in both intention and application.

This tension between empathy and tribal rationalization got me thinking about the mechanics of moral reasoning itself. What I want to do now is step back and examine whataboutism as a logical construct—not because the human stakes here aren't real, but because understanding how these arguments work might help us recognize when we're using them to avoid uncomfortable truths about ourselves. This isn't to diminish the human suffering I just witnessed, but to understand how our minds process and deflect from that suffering.

Whataboutism has become one of our most frequently dismissed rhetorical tactics. Like its cousin the ad hominem, it doesn't defend against criticism; it simply hurls a counteraccusation to deflect attention. The formula is simple: when criticized for something, respond by pointing to someone else's comparable or worse offense. “Sure, we did X, but what about when you or someone else did Y?” This is why whataboutism is often considered a fallacy: This counteraccusation doesn't address the truth of the original accusation; it's logically irrelevant even if the counteraccusation is true.

The Soviets perfected this technique during the Cold War. Whenever Americans criticized Soviet gulags, their standard response was, “And you are lynching Negroes.” This deflection became so predictable that it turned into a Cold War punchline. It's the rhetorical equivalent of responding to criticism with “Well, that's just like, your opinion, man.” It’s a way to dismiss without engaging

Whataboutism is usually considered out of bounds for a few reasons. First, it's a way to avoid criticism without needing to respond to the criticism. When Republicans respond to Trump's mishandling of classified documents by bringing up Hunter Biden's laptop, they're not arguing that Trump handled the classified documents appropriately. Instead, they are trying to shut down the conversation.

Second, it assumes that critics must be equally vocal about all wrongs everywhere, all the time. This “why aren't you protesting about Sudan?” argument implies that unless you're equally outraged about everything, your specific outrage is illegitimate. This is misguided: people are allowed to choose what they do and do not get agitated about.

But the most critical reason is one we were all taught as children: two wrongs don’t make a right. This is a cornerstone of deontological ethics, which judges actions by their inherent moral properties rather than through relative comparison. If Israel is displacing Palestinians unjustly, pointing to Syria's brutality doesn't magically transform that displacement into justice. If Hamas murders and rapes civilians, pointing to civilian casualties from Israeli airstrikes doesn't absolve Hamas of moral responsibility. The fundamental insight from deontology makes it clear why whataboutism can be illogical: one’s moral duties aren't nullified by others' failures to uphold their own.

But—and this is important—not all comparative arguments are created equal. The key distinction isn't whether one makes comparative arguments, but how and why they're deployed. Fallacious whataboutism seeks to terminate discussion and avoid accountability; legitimate whataboutism contextualizes, acknowledging criticism while expanding understanding.

The best form of whataboutism exposes genuine double standards. If someone applies one moral standard to enemies and another to allies, that's worth pointing out. When the UN Human Rights Council condemns Israel more times than all other nations combined, including North Korea, Syria, Sudan, Russia, and China, this screams selective outrage and hypocrisy. Something else is clearly going on.

Pointing out that your critic is hypocritical is not necessarily out of bounds or illogical. Just like with ad hominem, pointing out hypocrisy helps us make sense of the motives and character of the critic. Knowing someone is selectively principled helps us calibrate how much weight to give their moral judgments. That was why when public health experts treated BLM protests differently than other mass gatherings during COVID lockdowns, many people lost trust in their consistency. Rules that followed scientific necessity shouldn't suddenly bend for political expediency. Their hypocrisy cost them their moral authority and our trust.

Another legitimate form provides necessary context and nuance. When discussing Hamas's attack on October 7th, mentioning the blockade of Gaza doesn't justify the atrocities but helps explain the environment in which they occurred. Similarly, discussing the Second Intifada when talking about the diminished influence of the Israeli left doesn't make the Israeli public's mass rejection of the two-state solution any less concerning, but it acknowledges that political shifts don't occur in a vacuum.

Good whataboutism contextualizes wrongdoing. It asks whether our outrage is proportional and consistent. It questions why some human suffering dominates headlines while other suffering barely registers.

The true test of whether whataboutism is legitimate or mere deflection can be found in several questions: Does it acknowledge the original criticism rather than dismissing it? Does it expand understanding rather than shutting down conversation? Is it motivated by a desire for consistent standards rather than avoiding accountability? Does it compare genuinely related categories rather than making false equivalences?

So where does this leave us? With a few uncomfortable truths:

Whataboutism is usually a weak defense, regardless of who's using it. It doesn't absolve anyone of responsibility. It falls flat when comparing unrelated issues, when the scale differs dramatically, or when it's deployed to avoid addressing the original criticism. Most whataboutism abusers just want to change the subject.

Comparative arguments can still be worth making, however. While individuals are free to choose their causes, institutions that claim moral authority—like the UN, major news organizations, or public health agencies—should be held to higher standards of consistency. When academic institutions apply different standards to different conflicts, pointing out these double standards is legitimate. These institutions derive their credibility from claims of impartiality.

That said, I think we should all be a bit suspicious of our own whataboutist impulses. When I found myself mentally listing historical contexts while watching No Other Land, I wasn't evaluating the documentary's claims, I was trying to soothe my own discomfort.

The challenge for all of us is to hold onto both moral consistency and moral clarity. We can acknowledge the unique contexts of different conflicts while still applying universal principles.

I called myself a moral monster for immediately contextualizing Palestinian suffering. But maybe what would be truly monstrous isn't having those thoughts, but failing to realize that these thoughts mostly serve to justify another group’s suffering. Yes, context is sometimes needed to point out double standards and hypocrisy. But more often, whataboutist impulses are just psychological defenses against moral discomfort. The challenge isn't perfecting our arguments, then. It's having the courage to ask ourselves: are we seeking understanding, or just seeking relief?

Thanks for this!

I’m curious how the relationship between the arguer and the issue — to what extent does that impact the fallaciousness of the whataboutism?

To use some examples you reference, if one criticizes a Republican congressman’s defense of Trump’s documents handling and they in turn scream about Hunter Biden, that seems like unjustifiable whataboutism. In part, I suspect, because they are irrevocably attached to the issue. The deflection seems like unfair misdirection.

Whereas pressing “what about Sudan?” To a random American supporting the Palestinian cause (who let’s assume is otherwise untouched directly by either conflict), at face, does not seem like quite as fallacious a counterargument, as that person is opting into a moral issue with a degree of randomness (relative to them) that seems more valid to criticize with a whataboutist redirection.

So I’m curious how one’s relationship to the issue being discussed (and therefore their hypocrisy in being selective), plays a role, if any?

There is an interesting relationship between Whataboutism and the valid argument of Reductio ad Absurdum (RA). In RA, one shows that accepting the argument leads to unacceptable conclusions (in math a strightforward contradiction, in regular conversation, simply a conclusion the other party is unwilling to accept). Whataboutism is similar: if you are "condeming X, you should also accept condemning Y. If you do not, then your logic is flawed".

What makes Whataboutism a fallacy (assuming X and Y are equivalent, otherwise the problem is one of False Equivalence, not just Whataboutism) is the subtle logical move from "you should also accept condeming Y" to "you should have also actively condemned Y", which is not a logical necessity, since acceptance of condemnation does not neccesitate active condemnation