Understanding the Identity Game (Part II): Am I a Hypocrite?

I started my last post with a finger pointed at me.

My friend Paul Bloom accused me of being a hypocrite for deriding identity politics on the one hand and for the way I called out Jew-hatred on the other. My first response to my friend was that, because identity politics is the currency of the day, I was simply playing by those rules, even if I needed to hold my nose while doing so. But the more I thought about it, that response didn’t sit well with me. I don’t think I was only using identity politics cynically. Did I appreciate some aspects of identity politics after all?

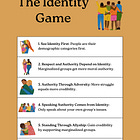

To reflect further, I tried to describe what I meant by identity politics. To do so, I conceived of identity politics as a game—the identity game—with a set of explicit rules. I am sure my set of rules is incomplete, but I hope it’s a start. I then steelmanned the game, trying my best to discuss them with charity. Here, too, I am sure I came up short. I hoped it could at least get a conversation going.

After playing …