In Praise of Punching Down

Yes, this essay will be praising punching down. But before you ready the pitchforks, let me explain.

I’m not suggesting we should be picking on people with less power—I'm only an asshole sometimes, not always. What I'm really advocating for is something that might sound drastic in today's climate: treating everyone's ideas the same way, regardless of their status, power, or identity. Call it intellectual universalism.

The principle of “not punching down” has become sacrosanct in academic spaces, holding them together like a rug ties a room together (sorry, couldn't resist). The idea seems noble enough: those with more power shouldn't attack those with less. The privileged shouldn't criticize the marginalized, white people shouldn't challenge people of colour, the wealthy shouldn’t mock the poor. You get the picture; it's about protecting the vulnerable. But like many well-intentioned principles, this one deserves unpacking.

I recently learned that sports writers coined the term “punching down” in the mid-20th century to describe boxers fighting above or below their weight class. It wasn't until the early 2000s that the term morphed into what we know today, a metaphor about power dynamics and protecting marginalized groups from abuse by the powerful.

Before beginning, let me be clear about one thing: my argument about punching down pertains specifically to the arena of science and truth-seeking. When the goal is getting at what's real and true, power dynamics shouldn't determine who gets to question what. This holds whether we're evaluating published research or examining truth claims made by student protesters about complex geopolitical conflicts. In these contexts, I'd argue that punching down isn't just permissible, it's essential for the pursuit of truth.

But I'll admit that different rules might apply in other arenas. Take comedy, for instance. Some argue it's poor form when comedians like Dave Chappelle poke fun at marginalized groups. Critics like George Carlin suggested the real issue with punching down in comedy isn't moral but artistic: it just isn't funny. Is the act itself unethical? That's a thornier question for another time. For now, let's focus on how this plays out in the pursuit of knowledge, where truth should be our north star regardless of who's seeking it.

And nowhere does this get more complicated (and more fraught) than in academia. Recent dustups have made me wonder whether we’ve lost the plot entirely.

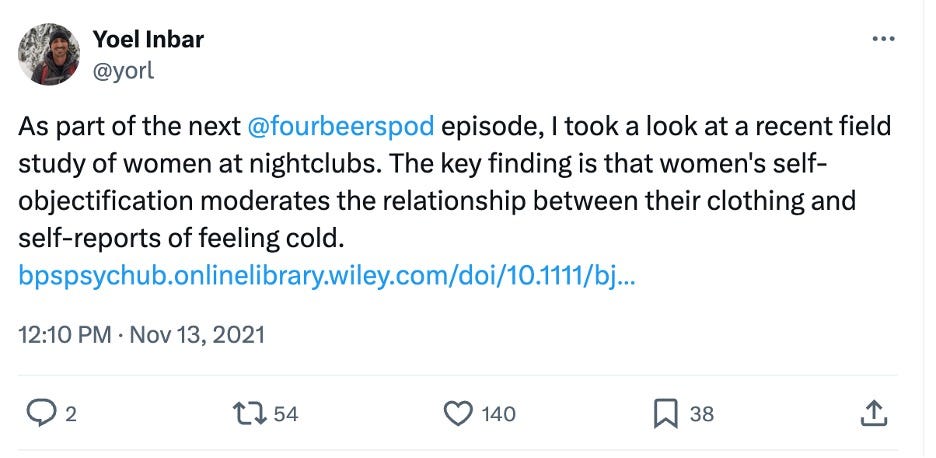

A few years ago, my friend, UofT colleague, and podcast co-host Yoel Inbar found himself in hot water for criticizing a psychology paper on Twitter and on our Two Psychologists Four Beers podcast. The paper claimed that attractive women don't feel cold outside of nightclubs on cold winter nights even when they're barely dressed. Some hot women, apparently, don't get cold. Yes, you read that right. And, yes, this was a real published article.

Yoel did what scientists are supposed to do: he scrutinized the methods and raised concerns about the analysis and conclusions. But instead of sparking a healthy scientific debate, something else happened instead. Because the paper's lead author was a graduate student and a woman, the response was a swift: "How dare you punch down!"