In Praise of Drinking (A Little)

I’m ba-a-ack. Did you miss me?

As much as I love you all, I need to actually work at my real job now. This means less time for Speak Now Regret Later, which is why this newsletter is now biweekly. It’s also why, at least till the new year, I’ll be republishing older essays.

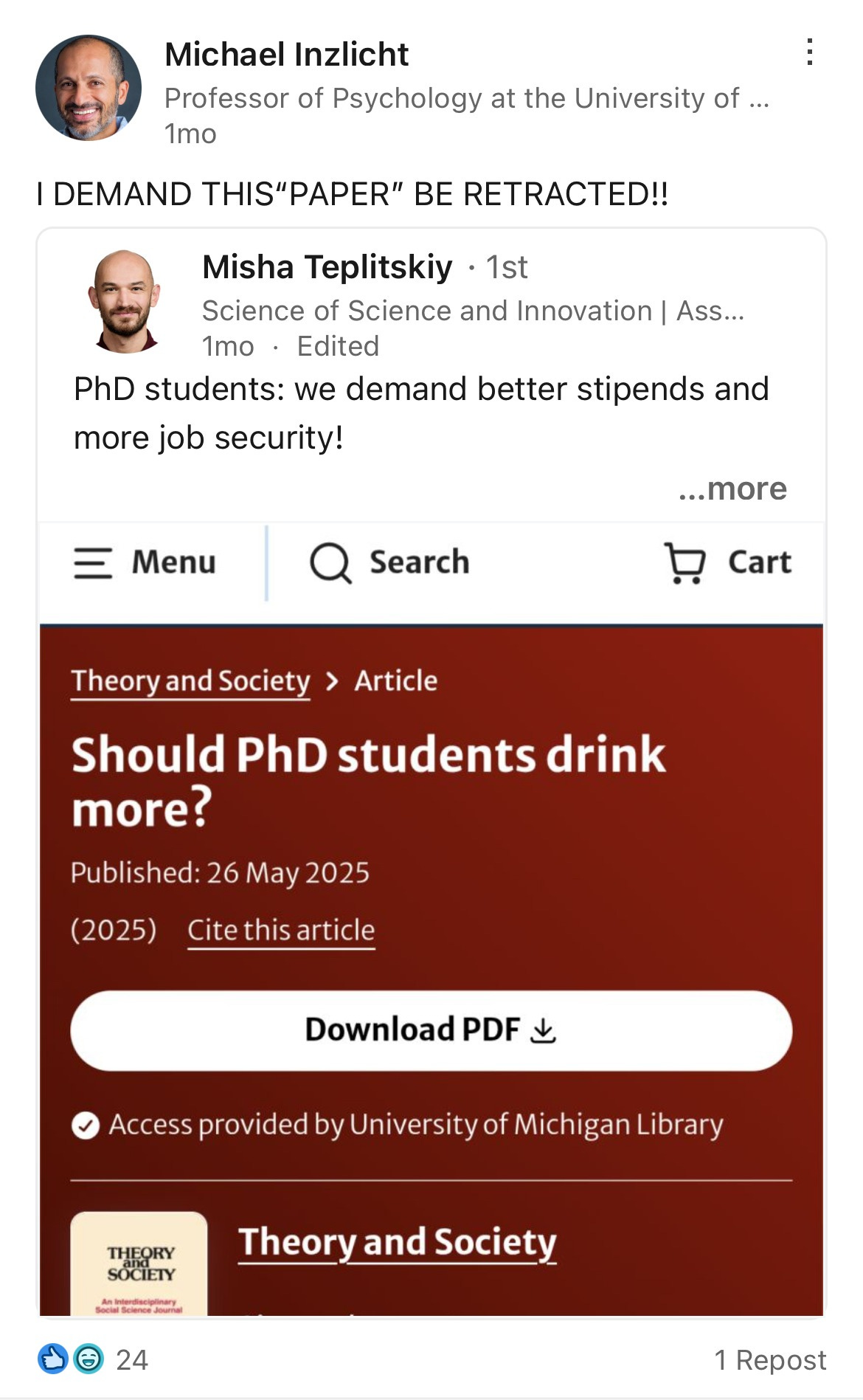

For today, I’m republishing last year’s most controversial piece: my essay on drinking culture in academia. Some of my colleagues were mad about it. But at least one person liked it—the editor at Theory and Society who invited me to submit and accepted the article. Alas, I now wonder if the editor regrets the decision, as the response online has been… mixed. Responses ranged from, “Wow this is wrong on so many levels” to “This is a fascinating article,” from “it’s shit like this that’s gonna drive me right over the edge” to “A sentiment I agree with.” One unhinged poster even demanded a retraction.

When I posted last year, it was behind a paywall, so very few of you read it. I’ve removed the paywall this time and curious to see how many folks will flame me in the comments. Want to know what all the fuss was about? Now’s your chance to find out.

Every Tuesday, after our department’s weekly seminar, faculty and graduate students head to a local pub. We sit, eat, and drink together for about an hour. It was a tradition that disappeared during the COVID-19 pandemic years but recently started up again.

When our pub gathering started up again, I. noticed something had changed. While most faculty ordered a beer or wine, our brilliant PhD students mostly stuck to water or perhaps ordered a tea. It marks a noticeable shift: before the world shut down, most of our students would have maybe one drink, but now it looks like they’re shunning alcohol altogether.

This change in drinking habits is part of a much broader pattern. Today’s young adults participate less in numerous life activities—from dating and driving to employment and social gatherings. My observation about departmental social hours thus reflects a larger societal recalibration of how young people assess risk and reward across many domains of life. So, while this change might not be specific to alcohol, the role of alcohol in academia deserves greater consideration.

I know what some of you are thinking: should alcohol really be part of professional academic life? It’s a fair question. The combination of alcohol and workplace dynamics can be thorny, sometimes leading to crossed boundaries or unprofessional behavior. Many institutions have moved away from alcohol-centered events entirely, worried about liability issues or creating uncomfortable situations. And there’s merit to these concerns: we’ve all heard stories of conference cocktail hours gone wrong or faculty parties that spawned years of departmental drama.

But I want to make the case that we’re missing something important in this rush toward safetyism and sanitizing academic life. These informal gatherings with alcohol might be more valuable than we realize. Borrowing heavily from Slingerland, I believe that moderate communal drinking—specifically in weak forms like beer and wine and in social settings with others—offers unique benefits for human connection.

Of course, I understand why young people are turning their back on alcohol. There’s nothing irrational about avoiding something with well-documented dangers. Alcohol is the source of much pain—violence, addiction, broken relationships, cancer and… well, impotence. And that’s not even the worst of it. Shall I tell you how bad my hangovers are? At 53 years old, if I drink two Juicy IPAs—or whatever is being brewed in the backwoods of Oregon these days—the next morning, I will have the runs, a splitting headache, and be a dick to my wife and kids for the entire next day. So, how can I praise this demon?

In our rush to be healthier, I can’t help but wonder if we are only considering the costs of alcohol and not its many benefits. If economists have taught me one thing, it’s that life is about balancing trade-offs. There are very few things in this world that are all benefits and no costs, or all costs and no benefits. Alcohol is no exception.

Let’s state the obvious first: alcohol can be fun! My late teens till my mid-thirties were dominated by alcohol-soaked weekends where my friends and I would sing, dance, eat, play, laugh. I recall more than a few times singing with my friends, arm-in-arm, to the jukebox playing some song I did not know the words to. Some of my best college, grad school, and postdoc memories were fuelled by booze. I am friends with many of these people still, and I have no doubt that alcohol forged some of these deep bonds. While I rarely get drunk any more, I still enjoy a glass or two of oat soda when I’m with friends.

Alcohol has been a mainstay in human society for a very long time. Whether celebrating some victory, mourning a loss, or just unwinding after a long day, alcohol has been there, smoothing the edges of life and making human interaction just a little easier. But if alcohol was merely fun, surely its many associated problems would be a strong argument against its continued use. I think most people would trade in a bunch of hazy memories of drunken singing with friends at some NYC dive bar for health and wellbeing. So maybe the kids are alright.

Or maybe the benefits of alcohol run deeper than the kids think. My friend Edward Slingerland, the Canadian-American historian and philosopher, explored this very possibility in his book, Drunk: How We Sipped, Danced, and Stumbled Our Way to Civilization.

Slingerland’s book starts with a vexing question: Given alcohol’s myriad social, personal, and health costs, why did our ancestors continue to consume it generation after generation? Why do we continue to drink to this day? It’s particularly puzzling because there are clear cultural, social, and even biological adaptations that could have prevented the proliferation of drinking. For example, temperance movements have failed to take root in nearly every place they have been tried. Genes for alcohol intolerance failed to spread widely despite being present in significant proportions among people of East Asian descent. Again, if alcohol only incurred costs, then individuals and groups who did not imbibe ought to have outcompeted individuals and groups who did, and the cultural practices and biological underpinnings of abstinence would have spread. But this did not happen.

Slingerland’s thesis is that communal alcohol consumption, at least in moderation, conferred real benefits that outweighed its costs. Those who drank together bonded, cooperated, and were more creative at deriving solutions to pressing problems in the brutal competition for resources and mates. The social cohesion fostered by communal drinking may have given early human groups an edge over more rigid, less cooperative rivals.

Alcohol helped us become better humans (except, of course, when it made some humans much, much worse). By lowering our inhibitions and our guards, we bonded with those around us and more readily cooperated with strangers. The result is that it helped foster trust and camaraderie both within and across groups, allowing for large groups to function as a single, cohesive unit. From ancient feasts to modern dinner parties, drinking together fosters a unique form of collective joy. It turns a group of individuals into something more cohesive, a unit that can think, create, and problem-solve together.

One reason alcohol may foster bonding within and between groups is by creating informational hostages. This concept originates from Diego Gambetta’s Codes of the Underworld. In Gambetta’s work, an informational hostage refers to holding crucial or compromising knowledge about others to secure their compliance or trust, especially in low-trust settings like criminal networks.

When we drink, we’re more likely to let our guard down, speak candidly, and even reveal things we might regret. Drinking together means everyone is potentially behaving in ways they’d rather not publicize, creating a mutual exchange of compromising hostages. This shared vulnerability builds trust as participants keep each other’s secrets, strengthening bonds.

To illustrate, I first met my now colleague, podcast co-host, and close friend Yoel Inbar at a conference in Washington, DC—back when we both had hair. One way we bonded was through a memorable night at the Presidential Reception, where too many free drinks on an empty stomach led me into an embarrassing situation I’d rather not detail here. Despite just meeting Yoel, he kept my secret, earning my trust. We still laugh about that night, and our friendship has only deepened over the years.

Slingerland also argues that alcohol makes us more creative. Creativity often comes from making unexpected connections, breaking out of rigid patterns of thought. This is where alcohol—again, in moderation—can be beneficial. It helps loosen the chains of our strict, logical thinking, and lets ideas flow more freely. Many of history’s great thinkers, from Hemingway to Beethoven, have turned to alcohol not to escape, but to inspire. I mean, even The Dude himself needed to stick to a pretty strict White Russian regimen to keep his mind limber.

What about other substances, like cannabis? It’s been used by humans for ages, but it never embedded itself in culture the way alcohol did. Could Slingerland’s logic apply to weed too? Yes and no. In theory, anything that loosens our inhibitions and gets us thinking more intuitively should have the same creative and societal benefits. But the problem is, cannabis affects people in wildly different ways—some love it, while others spiral into anxiety; for some it helps them turn their brains off, and for others it helps them focus. Plus, it’s tricky to dose. Alcohol, on the other hand, is consistent and predictable, which is why it’s been our social go-to for centuries.

But the even more fundamental question is: if what we value is social connection, creativity, and trust, why focus on drinking at all? Couldn’t we achieve these outcomes through substance-free alternatives, like group meditation, shared meals (without alcohol), or collaborative games? While these alternatives certainly have merit, Slingerland argues that alcohol uniquely combines several features that make it particularly effective: its reliable lowering of social defenses, its cross-cultural accessibility, and its deep ritual significance in human gatherings for millennia. The trust-building that occurs over drinks appears special: perhaps there’s something about the mutual vulnerability of mild intoxication that creates bonds difficult to replicate through other means.

Slingerland raises an important caveat about alcohol. Alcohol’s benefits are most readily seen when it is consumed the way our ancestors did—in weak forms, like beer and wine, and in the company of others. Think about how people in Southern Europe imbibe: they might have a glass of wine as part of a meal or to socialize, not an excuse to get hammered. Please do not read this and tell your friends that some professor suggested that downing shots alone in your dorm room is the secret to the good life. Distillation is a relatively new technology, and perhaps one that has done more harm than good. The key is moderation and community, not excess and isolation.

I want to emphasize that I’m not judging individual choices not to drink. There are countless valid reasons people abstain—religious beliefs, health concerns, family history, or simple preference. These choices deserve respect. My concern isn’t about individual decisions but about how our collective cultural shift toward health and safety might inadvertently sacrifice the time-honored tradition of bonding with colleagues. I mean, how else can you learn that your stern professor once got the cops called on him for throwing a TV off a rooftop patio?

All joking aside, I need to pause here and acknowledge something serious. While I’ve been singing alcohol’s praises, I’d be irresponsible not to mention its darker side. Beyond the hangovers I joked about earlier, alcohol ruins lives. It tears families apart, destroys careers, and kills people—either slowly through addiction and disease, or suddenly through accidents and violence. As someone who studies self-control, I’m acutely aware of how alcohol can hijack our decision-making processes, leading us to choices we’d never make sober. And in academic settings specifically, it can enable harassment, create power imbalances, and exclude those who don’t drink for religious, health, or personal reasons. These aren’t minor footnotes to my argument; they’re serious concerns that deserve real weight in any discussion about alcohol’s role in professional life.

So, where does this leave us? Should I be encouraging the PhD students in my department to drink during our social hours? Of course not! But I do think it’s worth having a more nuanced conversation about the role of alcohol in society. Demonizing it outright ignores the many ways it has contributed to human flourishing.

The challenge for academic communities isn’t whether to include or exclude alcohol entirely, but how to create inclusive social spaces where moderate drinking can coexist with engaging alcohol-free options. This means acknowledging both drinking and abstaining as valid choices deserving equal respect. When I witness our department’s social hour where drinkers and non-drinkers mingle comfortably, I see that such balance is possible.

Alcohol, like many things in life, is not inherently good or evil. It’s all about how we use it. In our pursuit of healthier academic spaces, let’s ensure we’re addressing alcohol’s genuine harms without losing sight of its benefits. After all, some of life’s greatest joys come with a little bit of risk, a lot of laughter, and the occasional hangover.

I agree with and relate to so much here as one who has merrily drunk, talked and danced many a night away in convivial company. But aren't you leaving out the new factor of ever present phones that can record every embarrassing transgression? Thankfully none of my escapades went viral past possibly next day gossip among a small group (which can be bad enough!) but nothing like the instant, permanent shame social media allows for. Unfortunately our younger generations have big brother in their pockets and on their minds 24/7.

It’s crazy that the view that drinking alcohol has pros and cons would be so controversial. Surely the panic speaks to just how much grad students — and Millennials in general — are repressing. Like, they can’t give the censor one night off.